I came across some very interesting new technology recently - specifically, the use of super-capacitors in automotive technology to solve a relatively simple problem - it is a good example of how innovative technology can find a place in day to day use, once the technology becomes cheap enough!

I encountered vehicle start assistance devices that employ super-capacitors! but first of all - what is a super-capacitor! they are also known as ultra-capacitors but basically, they are the same as any other capacitor - an electrical energy storage device that stores this energy in a dielectric field between two electrical ‘plates’. In function, similar to a battery, the difference being that a battery uses electro chemical storage. The super-capacitor however has a much greater energy storage capacity when compared to traditional types of capacitor - this greater capacity has led to super-capacitors being employed in some fields where a traditional battery may have been used, but where they can provide a specific set of advantages over and above.

Battery and Super(or Ultra) capacitor comparison (www.maxwell.com)

Super-capacitors, like many other technical innovations, were developed for military applications and they have several benefits - they have a much lower sensitivity to temperature and can actually still perform very well at very low temperatures (-40 degrees Celsius). They also have excellent performance with respect to power flow density - this means they can accept repeated high capacity charging and discharging and this is a clear advantage when compared to a chemical battery (which requires a chemical reaction to take place during the energy conversion process, this takes a finite length of time thus increasing the response time to a sudden power demand). Another advantage is the life cycle - even under harsh charging and discharging duty cycles, super-capacitors maintain their performance and their expected life is much longer than a chemical battery for the same operating conditions - 10 years is expected as a minimum!

Super caps and batteries compared (www.koldban.com)

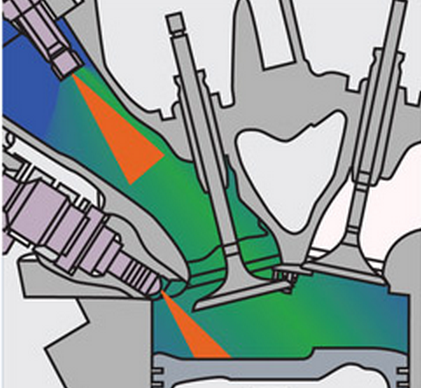

These devices are already in use in the automotive technology domain - in Formula 1 - the super-capacitor is ideal as a storage device for electrical energy from KERS and HERS energy recovery units. The high power flow density is ideal for this application as a replacement for the battery, or as a parallel device, in order to manage the complex energy flow and storage requirements during a race.

F1 KERS system layout that uses super-caps for energy storage (pre-2014 regulations system shown)

After some internet research I also found another interesting development for super-caps - vehicle flat battery assistance, also known as jump starting! I found some applications where super-caps have been employed for this - either as 'jump start' packs, or as units permanently installed on the vehicle alongside the chemical battery. In particular, commercial vehicles operating in extreme conditions at low temperature - Ice road truckers for example. In this domain they are ideal as the potential cost of downtime is very high for these vehicles. The additional weight and cost of a second storage device in addition to the battery is insignificant on a large truck or earthmover, especially when compared to the risk of not being able to start the vehicle at very low temperatures.

Super capacitor engine start module for permanent installation (www.maxwell.com)

Super-capacitors are ideal for mobile jump starting (as a jump start pack) as they require much less maintenance when compared to the use of a chemical battery. They are ideally suited for where a lot of energy is required in a short time i.e. to crank the engine, they can be charged quickly for use (seconds or minutes), hence the pack does not have to be maintained on charge when not in use.

Mobile engine start assist pack employing super capacitors (www.koldban.com)

However, if the super-capacitors are combined in a jump start package, along with some clever electronics - it is actually possible to charge the super caps from any available low voltage source - but how is this possible? well, the clever electronics is actually a DC-DC converter - which is a device capable of transferring electrical power at different voltages levels (input compared to output). These devices are already in use on certain vehicles, specifically those equipped with start-stop engine technology – the reason is that during an engine start , on a vehicle equipped with a traditional style electric starter motor, the starting current draw is sufficient to cause a 'dip' in the vehicle system voltage. Some systems are sensitive to this and may cause the action of a start/stop system to be more obvious to the driver. To avoid this, these electrical systems are connected to a DC-DC power supply system, which maintains a constant voltage and power level to avoid any perceivable response to voltage fluctuation for driver evident systems like HVAC, entertainment and driver information.

DC-DC converter as part of the stop/start system components (www.bosch.com)

Super-capacitors have a higher energy flow density but not a high energy storage capacity. So, it is possible to charge the capacitors with a relatively small power source, the DC converter acts like an electrical transformer to step up the voltage to charge the capacitors with sufficient energy for a single start operation. This is where the capacitors win over a battery due to their power delivery capability. Another interesting development is that using this power transform capability - the capacitors could actually be charged from the dead battery itself - as long as it has some voltage and power capacity. This seems difficult to comprehend but you should remember that the normal failure mode of a chemical battery involves its ability to deliver high power for starting - it is less often the case that the battery cannot deliver any power, even a small amount over a longer period of time, so this fact can be utilised for charging the capacitors for a start assistance situation.

The question now is, what does a package as mentioned above look like? I have been lucky enough to get access to the very latest device that incorporates all the features above - it is sold in the UK by Sealey (www.sealey.co.uk) who have an exclusive licence to sell the device with the manufacturer. The device is sold as a 'battery less' jump start pack - it is small and light when compared to a battery based device. It needs no maintenance and charges from the dead battery, or from another vehicle, or via USB. It can also be used with the vehicle battery open circuit, for situations where the battery is completely dead!

Batteryless jump start pack (www.sealey.co.uk)

Sealey electrostart charging from the 'dead' battery (www.autoelex.co.uk)

In service, it works well, the package is aimed at passenger car users and can supply about 300 amps, this is more than enough power and the device also includes a diesel glow plug support mode to allow pre-heating time.

Summary

My personal view is that this technology will definitely been seen more and more in Automotive applications. Modern vehicles have complex energy flow requirements, and increasing electrification will mean that an electro chemical energy storage device alone, may not fulfil all the technical requirements. So, my opinion is, that to support all the energy storage requirements and consumers in forthcoming vehicle platforms, a balance of energy storage technologies will be required – including traditional style wet batteries, advanced batteries with new chemistries, capacitors and even mechanical storage (hydraulic, pneumatic, flywheel).